[ad_1]

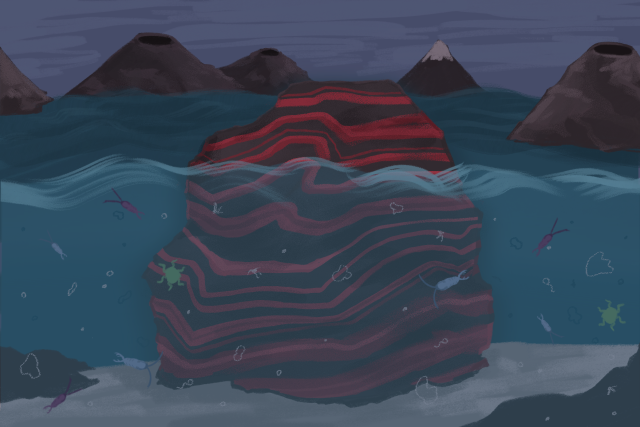

Transition metals encompass a class of elements vital to the basic functions of all living organisms. Many of the enzymes aiding in the production of energy in cells are dependent on these metals. A new study from researchers at the University of Michigan, California Institute of Technology and University of California, Los Angeles proposes that iron was the sole, original transition metal used by life for its various biological and metabolic functions.

In an interview with The Michigan Daily, Ted Present, senior scientific researcher and lecturer in geology at Caltech, described how the project came to fruition. Present said his co-author Joan Selverstone Valentine, professor emeritus of chemistry and biochemistry at UCLA, had a unique perspective on the abundance of iron in Earth’s early oceans, providing the initial inspiration for the project.

“(Valentine) heard some of the sorts of discussions that Jena and I, and some other researchers at Caltech took for granted, like, ‘Wow, the first half of Earth’s history had tons of iron in the oceans, and there’s no oxygen,’” Present said. “We sort of took this as a statement of fact for our fields. And Joan was like, ‘Well, wait, what? That has huge implications for how life lives in its environment.’”

Describing the process of working on the paper, Jena Johnson, U-M assistant professor of earth and environmental sciences, told The Daily in an interview that she and her co-authors met on Zoom to discuss the relative availability and potential biological use of different elements in the Archean — the eon during which life first formed on Earth — ocean.

“(We) started just going element by element and thinking about, what does the geological rock record say about the distribution of this element early on?” Johnson said. “What does geochemical modeling tell us, and what does biological usage tell us about whether or not this metal was even needed?”

Present and his colleagues used a U.S. Geological Survey computer program called PHREEQC — a software built to perform various geochemical equations in aqueous environments — to solve sets of thermodynamic equations. These equations look at the relative precipitation of various transition metals used by life forms today to determine how much of any given element would have been available for organisms to use in the Archean ocean.

“The bulk of the work was making sure that we had solubility constants or equilibrium constants … making sure those were consistent and reliable and then just using that program to calculate, in a complicated medium like ancient seawater — which we’ll never have a bottle of — what the solubilities and therefore what we thought the maximum concentrations of some of these metals might have been,” Present said.

By looking at the ratios of the maximum concentrations of various metals compared to iron, the researchers were able to determine the possibility that biological enzymes could have preferentially bound each transition metal.

“We found that in most cases, no, these simple molecules cannot bind any other metal,” Johnson said. “There would just be too much iron.”

The team then considered whether different categories of essential life functions in the Archean Eon could have relied on iron or whether other transition metals were essential to life functions. Johnson said she and her colleagues found that biological functions intrinsic to early life could have relied on iron.

“In basically all the cases of these metal ions doing a function that we think early life needed, (the metals they use) were exchangeable with iron at least or magnesium,” Johnson said. “For other functions, they were not so exchangeable. But then when we thought about the function — like detoxifying oxygen — well, detoxifying oxygen would be a function you just didn’t need it all. Or respiring oxygen, being able to breathe oxygen; you didn’t need that on early Earth.”

Johnson said working on this project had a significant impact on the direction of her research at the University. One of Johnson’s main research objectives moving forward is to consider the study’s findings through an experimental approach.

“Now we want to see experimentally: when do the metals precipitate, how much metal is left in solution and how much actually goes into solids and is more unavailable for life,” Johnson said.

Johnson also said she hopes to collaborate with other researchers at the University to study the ability of simple biological organisms to bind iron in the conditions of the early ocean.

“I also want to work with some chemists here at Michigan to try to test whether we can bind in these simulated Archean oceans — introduce some of these early biomolecules and see what metals bind to it,” Johnson said.

Rackham student Anisha Ghosh, a member of Johnson’s lab, is focused on conducting further experimental research on iron as life’s first transition metal. Ghosh described the two main aspects of her research: looking at the extent to which different metals precipitate and the metals preferred in the binding of early biological organisms.

“I try to simulate how much (of certain metals) is coming out of the (ocean) vents and — when it’s reacting with sea water — what is forming and whether it’s precipitating or not,” Ghosh said. “If it’s precipitating, how much is remaining. The second project would be, so whatever the remaining metals are, we try to figure out which metals are more preferential.”

Ghosh said she was drawn to this project because it integrates many of the areas of academic research that interest her.

“We can bring experiments and experimentally see, okay, things are forming and how things are forming,” Ghosh said. “And I was really, really interested in that.”

Present said the project was particularly exciting for him because of its multidisciplinary implications. He also expressed his hope that researchers of those various disciplines will respond to the paper.

“We hope it’s interesting to people who are both biologists and evolutionary biologists, biochemists as well as to geologists,” Present said. “There’s some assumptions people might have made for a while that we hope to take another look at.”

Daily Staff Reporter Bronwyn Johnston can be reached at jbronwyn@umich.edu.

Related articles

[ad_2]

Source link